Greater Kasai, a haven of peace for over 40 years, has become a conflict zone in ten months. Since the death of the leader Kamwina Nsapu, hundreds, perhaps thousands of people have been killed, at least forty-two mass graves have been discovered and over one million people have been displaced. In the face of an unprecedented insurrection, security forces have led a violent counterinsurgency campaign. Those responsible are known. They are the product of the darkest hours in the history of the Congo, of its two wars and the atrocities which have persisted ever since in the east of the country.

Eastern Congo has been surpassed by Greater Kasai, where the violence has reached a rare level of intensity. In ten months, the violence between followers of the traditional chief, Kamwina Nsapu and the security forces has affected five provinces. At least forty-two mass graves have been found, whilst new figures are released each by news agencies and humanitarian organizations. Over one million people have been displaced in Greater Kasai... Since January 2017, the insurrection has compounded interethnic conflicts, often manipulated for political purposes. As for the Congolese military, the Kamwina Nsapu has responded to them in a similar way to the Mai-Mai self-defense groups at the beginning of the first Congo war. The militia considers the military, especially those who were part of the rebellions supported by Rwanda, as invaders, just like the Rwandan army.

In 1996 and 1997, dozens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of the Rwandan Hutu refugees and Congolese civilians were massacred by Laurent-Desire Kabila’s Alliance of the Democratic forces for the liberation of the Congo (AFDL), en route to power in Kinshasa. For many, the subject has remained taboo and no crime has been prosecuted. This is the foundation of the culture of impunity in Congo. However, before the influx of millions of refugees, among which were those who committed the genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994, Eastern Congo was not that different from Greater Kasai. Despite some tragedies ![]() , the situation was mostly peaceful and violence was neither recurring nor widespread. And even as massacres by machetes occurred in neighboring Rwanda and Burundi, Eastern Congo resisted such fate as best they could. There were neither mass slaughter, rape, torture, or mass graves. Violence had not reached such a level in the DRC.

The officers deployed in the Greater Kasai began their careers during this period. Officers or « Kadogo

, the situation was mostly peaceful and violence was neither recurring nor widespread. And even as massacres by machetes occurred in neighboring Rwanda and Burundi, Eastern Congo resisted such fate as best they could. There were neither mass slaughter, rape, torture, or mass graves. Violence had not reached such a level in the DRC.

The officers deployed in the Greater Kasai began their careers during this period. Officers or « Kadogo ![]() », were for the most part soldiers from the east of the country who came to the “sacred” lands of the chief Kamwina Nsapu as part of the restructuring of the Congolese army.

», were for the most part soldiers from the east of the country who came to the “sacred” lands of the chief Kamwina Nsapu as part of the restructuring of the Congolese army.

The Kamwina Nsapu System

The day before his death, the traditional leader Kamwina Nsapu did not imagine that his land was about to witness such violent events. A member of parliament warned him: « If these people came to invade your kingdom and kill women and children … ». But Jean-Prince Mpandi did not want to hear any of this. He did not want to give in to the state authorities and its security forces.

It was a clash of two worlds: on the one hand, Kinshasa with its power, money and soldiers, and on the other hand, the marginalized countryside of Greater Kasai, where one still remembers the times when the traditional leaders were kings. Kamwina Nsapu wished to carve out a kingdom in Joseph Kabila’s DRC, return to the traditional ways and push back the state. Today, his militiamen are trying to accomplish his « dream » through political and discriminate violence. However, they are confronted by soldiers from the east.

TWO VIDEOS OF THE SAME CHILDREN'S MASSACRE NEAR VILLAGE KAMWINA NSAPU, 12 AUGUST 2016

Bloody assault against the Kamwina Nsapu : facing the children

Bloody assault against the Kamwina Nsapu : second view angle

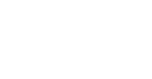

On May 29, 2017, the European Union adopted sanctions against nine (mostly political) Congolese figures. Regarding the area of Kasai, only one officer was named: General Eric Ruhorimbere ![]() . As head of operations, he was accused of using excessive force and the arbitrary executions committed by his soldiers in Greater Kasai. Quotation marks or not

. As head of operations, he was accused of using excessive force and the arbitrary executions committed by his soldiers in Greater Kasai. Quotation marks or not

Although today, he is based in Mbuji-Mayi in Easter Kasai, Eric Ruhorimbere participated in all the rebellions in the east of the country, including those which were the most denounced by the UN ![]() for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Wearing sunglasses, with a rigid posture, Eric Ruhorimbere is not of the hesitant kind.

for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Wearing sunglasses, with a rigid posture, Eric Ruhorimbere is not of the hesitant kind.

First, during the first Congo war ![]() , he chose the AFDL

, he chose the AFDL ![]() , the rebellion, supported by Rwanda and Uganda, which led a military campaign of exceptional violence and overthrew the teetering regime of the aging President Mobutu in a few months. His people, the Banyamulenge

, the rebellion, supported by Rwanda and Uganda, which led a military campaign of exceptional violence and overthrew the teetering regime of the aging President Mobutu in a few months. His people, the Banyamulenge ![]() , were attacked of the Rwandan Hutus of the ex-FAR / Interahamwe

, were attacked of the Rwandan Hutus of the ex-FAR / Interahamwe ![]() and by Congolese militia

and by Congolese militia ![]() . He found himself in a logical alliance with Rwanda. The new regime in Kigali wanted to push the Hutus, ex-FAR as refugees, far from its borders. The Banyamulenge wanted to repel them from what they considered as their land.

. He found himself in a logical alliance with Rwanda. The new regime in Kigali wanted to push the Hutus, ex-FAR as refugees, far from its borders. The Banyamulenge wanted to repel them from what they considered as their land.

Major Report RFI, 06 October 2016 (original version)

Lemera, 20 years of impunity in the Congo. The story of the first crime in the first war

Eric Ruhorimbere was still a rebel fighter when he joined the RCD ![]() against the young regime of Laurent-Désiré Kabila [Tooltip father of the current president] who turned against his old allies in Kigali and Kampala. It was the beginning of the second Congo war

against the young regime of Laurent-Désiré Kabila [Tooltip father of the current president] who turned against his old allies in Kigali and Kampala. It was the beginning of the second Congo war ![]() . Eric Ruhorimbere was suspected of being part of the Banyamulenge commanders who had participated in the assassination of 36 Congolese officers in the airport of Kavumu in South-Kivu on August 4, 1998, and in the massacres of Makobola and Kasika in South-Kivu from 1998 to 1999.

. Eric Ruhorimbere was suspected of being part of the Banyamulenge commanders who had participated in the assassination of 36 Congolese officers in the airport of Kavumu in South-Kivu on August 4, 1998, and in the massacres of Makobola and Kasika in South-Kivu from 1998 to 1999.

At the end of the war, Eric Ruhorimbere had no intention of letting go of his « feifdom » in the East. Like his fellow soldier Laurent Nkunda ![]() , in 2003, he refused to be « integrated », that is to say mixed with other former belligerents and sent to another province of the DRC. It is the case of many Rwandophone officers

, in 2003, he refused to be « integrated », that is to say mixed with other former belligerents and sent to another province of the DRC. It is the case of many Rwandophone officers ![]() . For them, it was out of the question to let their enemies provide security for their families and their properties in North and South Kivu. Yet, the objective was to create a new national and republican army. That was what the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (AFDRC) had to become.

. For them, it was out of the question to let their enemies provide security for their families and their properties in North and South Kivu. Yet, the objective was to create a new national and republican army. That was what the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (AFDRC) had to become.

In 2004, whilst taking over Bukavu, Eric Ruhorimbereaux was unsurprisingly by the side of the rebel colonel Jules Mutebutsi. Just like him, he had to flee to Rwanda for a period of time. Three years later, he joined the CNDP ![]() , the rebellion of Laurent Nkunda. After 10 years of impunity, these feared officers did not hesitate to use force, even in front of blue helmet soldiers, like in Kiwanja in 2008.

, the rebellion of Laurent Nkunda. After 10 years of impunity, these feared officers did not hesitate to use force, even in front of blue helmet soldiers, like in Kiwanja in 2008.

"On November 4 and 5, 2008, approximately 150 people had been killed in the town of Kiwanja, one kilometer away from the peacekeeping forces of the United Nations. This event is one of the worst massacres witnessed during the last two years in North Kivu."

Massacres in Kiwanja, the inability of the UN to protect the civilians, HRW, December 2008.

The CNDP fighters had undertaken the systematic execution of those accused of belonging to, or supporting the Mai-Mai ![]() self-defense groups

self-defense groups

Report on serious violations of human rights committed in Kiwanja, in November 2008, UNJHRO ![]() , September 2009

, September 2009

One shadow cast on this journey was the M23 ![]() . Unlike other rebel movements in eastern Congo, Eric Ruhorimbere did not rally this one, even if he had long worked under the command of Bosco Ntaganda, nicknamed « Terminator », who was at the origin of the 2012 revolt. While the M23 fled to Uganda and Rwanda, Eric Ruhorimbere was rewarded for his loyalty towards the AFRDC. Although he was part of the generals considered by MONUSCO as « red

. Unlike other rebel movements in eastern Congo, Eric Ruhorimbere did not rally this one, even if he had long worked under the command of Bosco Ntaganda, nicknamed « Terminator », who was at the origin of the 2012 revolt. While the M23 fled to Uganda and Rwanda, Eric Ruhorimbere was rewarded for his loyalty towards the AFRDC. Although he was part of the generals considered by MONUSCO as « red ![]() », he was promoted to general in 2014. Two years before the end of his second and last mandate, Joseph Kabila appointed him alongside other « red» generals in the center and west of the country. Was this a coincidence? It was in these regions that the population was most likely to revolt against his attempt to stay in power.

», he was promoted to general in 2014. Two years before the end of his second and last mandate, Joseph Kabila appointed him alongside other « red» generals in the center and west of the country. Was this a coincidence? It was in these regions that the population was most likely to revolt against his attempt to stay in power.

The other reason why the government moved the generals from the east to the west, is because it wanted to prevent these ex-rebels from turning against president Joseph Kabila, by notably isolating them away from their bases, Rwanda and Uganda. The redeployment was carried out to the great dismay of the Kasaians who considered these soldiers to be foreigners, “Rwandans” seen as criminals and oppressors. One of the first to open the east-west route was general Obed Rwibasira ![]() , up until now commander of the military region of North Kivu. He was accused of allowing the Rwandan army to make incursions into Congolese Territory. He was transferred to Mbuji-Mayi in 2004 in Kasai-Oriental, then to Kananga, in Kasai-Central. When the M23 crisis broke out, the military command feared that some of its officers would join the mutineers. Among these units was the 811th regiment

, up until now commander of the military region of North Kivu. He was accused of allowing the Rwandan army to make incursions into Congolese Territory. He was transferred to Mbuji-Mayi in 2004 in Kasai-Oriental, then to Kananga, in Kasai-Central. When the M23 crisis broke out, the military command feared that some of its officers would join the mutineers. Among these units was the 811th regiment ![]() , commanded by colonel Innocent Zimurinda, who was also transferred to Kananga in April 2012. Many of these Rwandaphone officers have been in the Grand Kasai for almost ten years.

, commanded by colonel Innocent Zimurinda, who was also transferred to Kananga in April 2012. Many of these Rwandaphone officers have been in the Grand Kasai for almost ten years.

Massacre in Tshimbulu, January 2017

"2017 in Congo has brought rivers of blood. As they say, you get what you look for"

Extract of the video of a soldier filmed on January 4, 2017, in Tshimbulu

In Tshimbulu, in Central Kasai, the locals call the series of mystical attacks and bloody repression « catastrophes ». This is what their daily lives have been like for the past few months. The first « catastrophe » occurred when the Kamwina Nsapu was alive. On August 8, 2016, his followers assaulted the police station and other public buildings. These clashes caused about a dozen deaths. But it was from January 2017 that « the rivers of blood» started flowing. In five months, the militiamen have attacked ten times and were massacred in Tshimbulu and in the surrounding localities. Of the forty-two mass graves that the UN has documented to date, nineteen were discovered in Tshimbulu.

"- I have never seen corpses of soldiers, and I don’t know if they have a way of hiding them. But I saw civilians. Little children...

- And what do they do with the bodies?

- They bury them. They bury them"

Extract of the testimony of a Tshimbulu local received by RFI on 11 March 2017

Interview RFI, 11 March 2017 (original version)

A local of Tshimbulu recalls the mass graves dug by soldiers around its locality

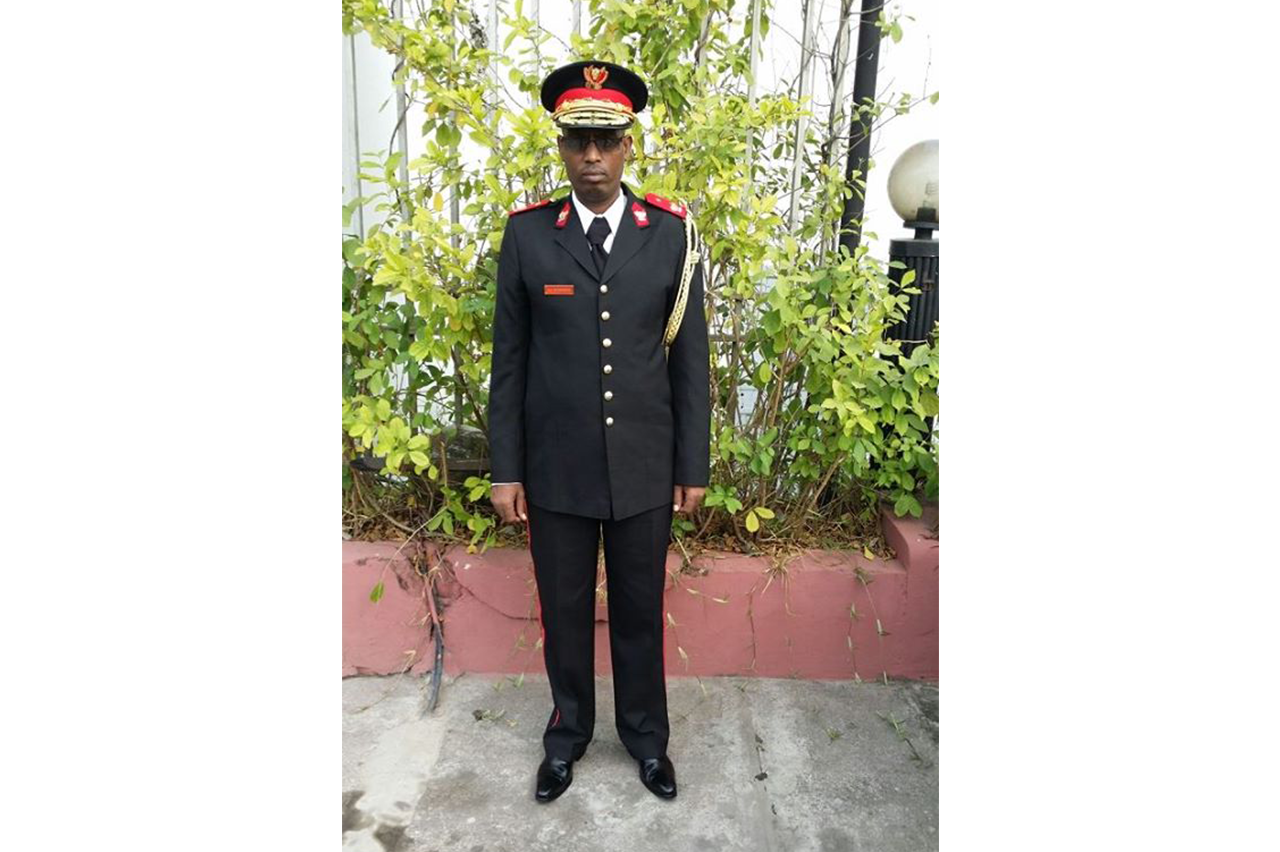

Since January 2017 and the discovery of the mass graves, the officer in charge of operations in Tshimbulu is François Muhire Sebasonza ![]() . The Congolese military justice accused him of being one of the main authors of a massacre committed four years ago in North Kivu.

. The Congolese military justice accused him of being one of the main authors of a massacre committed four years ago in North Kivu.

February 2013 in Kitchanga, North Kivu, where François Muhire’s regiment was formerly known as the 812th, clashes turned into massacre of civilians, with at least 200 deaths and hundreds of houses burnt or pillaged.

François Muhire and his men suspected the civilians of supporting a rival armed group which had to be integrated into the Congolese army. The Congolese military justice identified fourteen officers among which François Muhire, as the main culprits.

Worse, the United Nations Group of Experts accused François Muhire of distributing weapons to civilians from his community while his superiors called on him to kill residents of Kitchanga. According to the UN experts, after having been attacked by an armed group, François Muhire retaliated by massacring residents of Kitchanga who were accused of being accomplice to the rival armed group. In July 2013, this information was shared by the UN Group of Experts with the UN Security Council.

After the massacre of Kitchanga, François Muhire and his men disappeared from the scene. The soldiers of the 812th regiment were re-deployed to Kananga, in Central Kasai. It was this same year that the soldiers were interrogated for the first time. Three years later, at the beginning of 2016, the Congolese military justice had a list of fourteen suspects among which was François Muhire. Although over 400 witnesses were interviewed, the main perpetrators of the massacre have never been arrested. Pressured by the UN ![]() , the Congolese military prosecutor in charge of this delicate case, colonel Jean Baseleba Bin Mateto, asked his superiors to bring these fourteen officers back to Goma. The judge identified the names of their new units and their deployment posts, but according to sources close to the case, he hesitated because he feared reprisals.

, the Congolese military prosecutor in charge of this delicate case, colonel Jean Baseleba Bin Mateto, asked his superiors to bring these fourteen officers back to Goma. The judge identified the names of their new units and their deployment posts, but according to sources close to the case, he hesitated because he feared reprisals.

In May 2016, a few weeks after his request, colonel Bin Mateto was transferred to the province of Central Kongo, far away from Goma and this case. Officially, according to the information received by the military magistrate, the 812th regiment was supposed to be in Katanga, far from Greater Kasai. However, when the Kamwina Nsapu crisis broke out, at least four of the officers suspected of the massacre of Kitchanga were in Kananga, then in Tshimbulu. Mass graves multiplied in their territories.

From August 8, 2016 to January 4, 2017, Tshimbulu did not witness any clashes. Colonel Muhire and his men arrived and just after Christmas Eve in December 2016, the militia launched their first attack.

"We did not have any problem with you. In 2017, you wanted to rejoice at the beginning of this year. Now you see, Kamwina Nsapu? It is you and us."

Extract of a video filmed by a soldier, Tshimbulu, January 4, 2017.

For the Kamwina Nsapu militia, Rwandophone officers of the AFDRC were « Rwandan », foreigners who had to be chased from their « sacred land ». Their arrival was seen as an invasion. The militia attacked the city of Tshimbulu almost every month, where the soldiers were stationed. Under the orders of Colonel François Muhire, the FARDC responded with rocket-launchers. In the January 4th video, a soldier says it himself.

"These are arms. The rocket hit him. This other guy, the rocket almost blew him to pieces. He is the one responsible for this situation. He is the one who called for this musical piece [referring to the rocket] and we delivered what he requested"

Extract of a video shot by a soldier, January 4, 2017, Tshimbulu.

After the assault on February 9, 2017 and the subsequent repression, the joint office of the United Nations for Human Rights was publicly alarmed for the first time by reports about the use of these rocket-launchers by the army. In the video filmed by a soldier on February 9, 2017, there was seemingly only one real firearm in the weapons seized from the militia, it was a 12-gauge old hunting rifle. The quality of the image was very poor, but the soldier inspects the « weapons ». There were three, perhaps four. All of the other weapons were wooden toys.

Reaction of the Minister of Human Rights to the use of rocket launchers (original version)

His cell phone in hand, the soldier also inspects the bodies of the victims. An adolescent with her legs spread apart, loincloth up. A second one, older, same position, skirt up. Close-up. The first one seemed to have received a bullet in the head. The second one’s upper body is covered in blood. The author of the video filmed them closely and from all angles. A child’s face is disfigured. He circles around her body. Two young people are seen with red banners. The second one’s pants are down. Close-up. Five victims, among which women and children, wooden toys in hand - « mystical weapons » or traditional weapons, but no weapons of war. In the background, a policeman and serviceman are talking away from the one filming. He moves among them to film the bodies.

"- Was it the population that pushed them to do what they did?

- Come, come and see

- We will not move from here. This is work.

- I’m not able to find other work.

- Are there even girls among them?

- Girls too, papa !"

Extract of a video shot by a soldier, Tshimbulu February 2017

Massacre at Tshimbulu, February 2017

The mass graves of Tshimbulu are easy to find. All the locals talk about them. They are always near the road. Nearby, on the track, there are blood trails and « brain matter ». In some instances, one can see arms, legs, entire bodies, which are improperly buried or not buried at all. The ground is freshly stirred. These graves are found, most of the time, less than five kilometres around Tshimbulu.

Report RFI, 20 March 2017 (original version)

The inhabitants of Tshimbulu traumatized by the discovery of a mass grave

During the first months, the Congolese army seemed to lack logistical means, and requisitioned civilian trucks to transport the soldiers or the victims’ corpses. Therefore, on 12 August 2016, one of these civilian trucks is visible in the background of one of the videos of the bloody assault against Kamwina Nsapu. But everything changed after December 2016. On 21 December, « Mwanza Lomba » massacre occurred. A video of this massacre was shot by one of the soldiers present ![]() . In this video, which shows the misdeeds of the army, one of the soldiers speaks about « Bureau 4 ». This is the name of the logistics office within the Congolese army, covering trucks and supplies. A source from within the Congolese staff has since confirmed that it had been decided, between the end of December 2016 and the beginning of January 2017, to deploy military trucks in the zone to support the army’s operations. One of these trucks followed the soldiers who, on 21st December 2016, executed suspected militiamen near Mwanza Lomba. Since January 2017, locals in Central Kasai have been reporting the presence of these military trucks. When they travelled at night, the next day villagers would discover mass graves.

. In this video, which shows the misdeeds of the army, one of the soldiers speaks about « Bureau 4 ». This is the name of the logistics office within the Congolese army, covering trucks and supplies. A source from within the Congolese staff has since confirmed that it had been decided, between the end of December 2016 and the beginning of January 2017, to deploy military trucks in the zone to support the army’s operations. One of these trucks followed the soldiers who, on 21st December 2016, executed suspected militiamen near Mwanza Lomba. Since January 2017, locals in Central Kasai have been reporting the presence of these military trucks. When they travelled at night, the next day villagers would discover mass graves.

Report RFI, 20 March 2017 (original version)

Near the locality of Tshienke, next to Tshimbulu, locals have discovered graves after the passage of a military truck.

In Tshimbulu, there was another name which everyone used to whisper, the name of a lieutenant. Julle Bukamumbe, who claims to be a native of Kazumba, in Central Kasai. He appears to be a « real » Kasaian speaking Tshiluba, as well as the two other languages spoken in the army, Lingala and Swahili. « Lieutenant Julle » came one day with a commander in one of the military trucks, towards the end of December 2016. The commander then travelled with his truck across the territory of Dibaya, but the lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe stayed. He was already there when Colonel François Muhire was seen for the first time in Tshimbulu.

Lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe does not hide - he is even seen casually chatting with locals. He used to complain about the bad relationships with the « Rwandans », favored by the hierarchy. Like the Kamwina Nsapu, he accused his rwandophone fellow soldiers of being « foreigners » ![]() .

.

But Lieutenant Julle had more precise concerns. In the beginning of March 2017, according to a military source, he complained directly to Kinshasa about the shortage of food, to the disappointment of General Eric Ruhorimbere, who sent him back to Kananga. Other sources claim he plundered a village. He also worked for a local authority. Julle Bukamumbe does not seem to be very popular.

Lieutenant Julle « killed many », according to the villagers, and not only in Tshimbulu. Inhabitants of the Dibaya’s territory, where the insurrection started, say they recognise his voice in the videos of the deadly assault against the chief Kamwina Nsapu, on 12 August 2016. Three sources say they were able to identify him. Among them the author of one of the two videos, the most formal.

"Here, we are at the crossroad where one of the paths leads to the district of the chief Kamwina Nsapu."

Bloody assault against the chief Kamwina Nsapu : report of the situation

We act as para-commandos of MDRC battalions, 5th operational brigade. We will finish him."

Video attributed to Lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe, in the bloody assault against the court of the Chief Kamwina Nsapu on 12 August 2016.

According to the information received by RFI, Lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe was close to She Kasikila, the former leader of the 5th brigade. Ten years before, he had apparently even fought under the orders of She Kasikila within this unit.

The brigades became regiments in 2010 – 2011. And the members of the 5th brigade found themselves in the 811th regiment of MDRC. In 2012, they were transferred to Kananga to prevent them from rallying with the M23 rebellion ![]() . Was Lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe among them? One thing is certain, in August 2016, he was present in Kananga. And for the soldiers and policemen present, the situation was critical, because they are all blamed for their gullibility and lack of efficiency. According to a local director of security services, at the time, servicemen and policemen were struggling to oppose Kamwina Nsapu’s “children”, who were merely armed with wood sticks. Some of those policemen and servicemen, hailing from Greater Kasai, rallied with the militiamen, which gave the authorities cause for concern. Other agents from that area, or from provinces with the same beliefs as Kamwina Nsapu, feared their « mystic powers », their wooden weapons and the « baptism » supposed to make them invincible.

. Was Lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe among them? One thing is certain, in August 2016, he was present in Kananga. And for the soldiers and policemen present, the situation was critical, because they are all blamed for their gullibility and lack of efficiency. According to a local director of security services, at the time, servicemen and policemen were struggling to oppose Kamwina Nsapu’s “children”, who were merely armed with wood sticks. Some of those policemen and servicemen, hailing from Greater Kasai, rallied with the militiamen, which gave the authorities cause for concern. Other agents from that area, or from provinces with the same beliefs as Kamwina Nsapu, feared their « mystic powers », their wooden weapons and the « baptism » supposed to make them invincible.

"One day, a young girl came with a rifle-shaped wooden stick. She said to a serviceman: give me your weapon or I will kill you, and he gave it to her."

Testimony of a policeman, Kananga, January 2017.

On 12 August 2016, servicemen and policemen were sent to assault Kamwina Nsapu’s house. They had to demonstrate that they knew how to lead operations.

"The president of the Republic has to know that his troops are in Kananga because he is told that we lie to him"

Extract of the video attributed to the lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe, 12th of last August, in the bloody assault against the chief Kamwina Nsapu.

In two videos shot on 12 August 2016, the day Kamwina Nsapu died, the name of the president Joseph Kabila is mentioned. There is the video attributed to the lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe, and a second from another soldier, in Kamwina Nsapu’s courtyard. Facing his dead body, cell phone in hand, the soldier accuses Jean-Prince Mpandi (Kamwina Nsapu) of disrespect towards the head of state. In the five other videos of the exactions committed by the security forces, of which RFI has received a copy, there was no reference to president Kabila. The latter was in Kananga three weeks before the death of chief Kamwina Nsapu, to inaugurate a solar plant, but also to enquire about the crisis.

"Here, we are in the village of Mwanza Lomba. Today, we have come across the militiamen. We proved them that force remains on the side of the law. We will go after them indefinitely. We will go after them until the day they are all exterminated."

Extract of the video of a Congolese serviceman, Mwanza Lomba, Kasai-Oriental, 21 December 2016.

Massacre of Mwanza Lomba

18 February 2017 saw the first real blow to the Congolese government. That day, a video of “Mwamza Lomba” was reported on social medial. Right away, the American and French governments stepped up to demand an investigation. The Congolese Communications Minister, Lambert Mendé, denounced “ridiculous editing” and spoke of “malicious rumours”. To support his view, he even produced the opinion of an expert, “M.K”. Strangely, his expertise is entitled “Manipulation of Tshimbulu’s images”.

"It is not his duty to prove the innocence of MDRC (…). It is up to the accusers, who are unknown until now, to prove these facts"

Report of the Communications Minister Lambert Mendé, 20 February 2017.

Despite official denials, the Congolese military justice decided to investigate. The joint office of the United Nations for Human Rights was ready to assist it. The demand was accepted on 25 February 2017. However, when it was about to go out into the field, the UN team was kept away. It was claimed that the mission order paperwork had “not been filled”. The Congolese military magistrates continued their work by themselves.

On 20 February 2017, when the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Jordanian Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, asked for the slaughtering to end in Greater Kasai, he referred to the Mwanza Lomba video. Investigators of the UN Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO ![]() ) led many missions on the ground to verify the allegations of the mass graves. At the time, they were not alone. Blue Helmets and other sections of the UN mission were also involved in the investigations into the exactions. However, there were many restrictions and Blue Helmets say they were threatened with guns by Congolese soldiers whilst attempting to travel to the presumed sites of mass graves.

) led many missions on the ground to verify the allegations of the mass graves. At the time, they were not alone. Blue Helmets and other sections of the UN mission were also involved in the investigations into the exactions. However, there were many restrictions and Blue Helmets say they were threatened with guns by Congolese soldiers whilst attempting to travel to the presumed sites of mass graves.

"In light of recurrent reports which demonstrate serious violations and with the recent discovery of three new mass graves, I urge the council to establish a commission of inquiry to examine these allegations."

Extract of the speech of Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, high commissioner of the United Nations, before the UN human rights council, 8 March 2017

Ten days after the appeal of the high commissioner, on 18 March 2017, the Congolese military justice said it had arrested seven suspects, all servicemen ![]() , and discovered two mass graves. It was no longer a matter of crude framing. The Congolese auditor general, General Joseph Ponde, enumerated a long list of counts: war crimes by murder, mutilation, cruel inhuman and degrading treatment, and the refusal of the denunciation of an infringement by military jurisdictions or individuals. But he insisted on the context, this asymmetrical war “imposed” on the security forces, and on the fact that militiamen disrespected the symbols of the state, and were armed killers. Thus, for two provinces, the military magistrate provided a number of weapons seized from the militiamen: five firearms, including three AK47, three bombs and a « large quantity » of bladed weapons in Central Kasai and twelve 12-gauge trifles, an AK47 rifle and a « large quantity » of bladed weapons in East Kasai.

, and discovered two mass graves. It was no longer a matter of crude framing. The Congolese auditor general, General Joseph Ponde, enumerated a long list of counts: war crimes by murder, mutilation, cruel inhuman and degrading treatment, and the refusal of the denunciation of an infringement by military jurisdictions or individuals. But he insisted on the context, this asymmetrical war “imposed” on the security forces, and on the fact that militiamen disrespected the symbols of the state, and were armed killers. Thus, for two provinces, the military magistrate provided a number of weapons seized from the militiamen: five firearms, including three AK47, three bombs and a « large quantity » of bladed weapons in Central Kasai and twelve 12-gauge trifles, an AK47 rifle and a « large quantity » of bladed weapons in East Kasai.

Interview RFI, 13 janvier 2017

La ministre congolaise des Droits de l’homme explique la lenteur des enquêtes

However, in March 2017, the United Nations had another concern. Since March 12, the UN had not received any news of their experts, Michael J. Sharp and Zaida Catalan, for whom they had been searching. Once again, the Congolese government limited access to Central Kasai. It deemed it too dangerous to let foreigners travel around without informing them beforehand or even without an official military escort. The same day it launched an investigation into the disappearance of Michael J Sharp and Zaida Catalan. Kinshasa gave a report before New York on this « kidnapping ».

Until then, the Congolese authorities rarely used to release information on the losses inflicted by the Kamwina Nsapu on the security forces. But at the end of March 2017, the police confirmed that during the week-end of 23 and 24 March, at least 39 policemen were killed. They were caught in an ambush in Kamuesha, in the province of Kasai, on the axis of Tshikapa-Kananga. Before being killed, they were apparently taken prisoner, along with their trucks full of law enforcement equipment.

Police officers captured by Kamwina Nsapu militiamen

The sound is of a bad quality, but in this video, presumed Kamwina Nsapu militiamen interrogate seated policemen, some of whom are barefoot. One of them presents himself as a journalist and even gives his name.

"I am Grégoire Muambawa Tshitala. I am doing this report. I testify that these people and their property were caught. We all are the inhabitants of the village, and we can see what they were transporting. There are their cooking utensils, their mattresses are there, their bags too. They have their weapons."

Extract of the video of the policemen captured, Kamuesha, 23 or 24 March 2017.

The police announced another video, that of the execution of the prisoners. The international community condemned it, without any more information.

"This is the general who leads the troops. He is the leader of the traitors. He is the one sent to destroy this village. Here he is. These people that you see are sent to destroy the whole village or the whole country of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Look at them. They are the real rebels who came to destroy this country."

Extract of the video of the policemen captured, Kamuesha, 23 or 24 March 2017

Grégoire Muamba wa Tshitala interrogates the policemen. The talk is in Tshiluba, the local language. It is a simple questioning on the purpose of their missions. The policemen seem to originate from different provinces. One of the villagers insists that the policemen speak in Tshiluba. They are accused of being traitors.

A month later, on 24 April 2017, the video of the captured police officers was presented to the media by the spokesman of the police and the Communications Minister. It was broadcast with two other recordings of exactions attributed to Kamwina Nsapu: a short video of a beheading and the video of the execution of the two UN experts, missing since 12 March.

"The president of the Republic told (…) the Minister of Justice to take the provisions pertaining to his function urgently in order for the competent prosecutors’ office to initiate an investigation (if not already done)."

Office of the President of the Republic, 17 April 2017

For the Congolese authorities, these videos put an end to the debate. The Kamwina Nsapu were viewed as « terrorists » and the main culprits in the acts of violence in Greater Kasai. On 15 May 2017, the army spokesman provided a report on the operations since the beginning of March: 390 militiamen, 39 servicemen and 85 police officers had been killed.

"Our troops respect the International humanitarian law and human rights. (…) we have operated in a professional way"

Statement by the Congolese army spokesman, on 15 May 2017.

Since the UN High Commissioner called for an international investigation, on 8 March 2017, the « most visible » officers of the Congolese army had gradually disappeared from the field. Neither Colonel François Muhire nor the lieutenant Julle Bukamumbe are present in Tshimbulu today. In Kananga, the operational control has essentially been replaced. They all seem to have been redeployed to new fields of operations.

As for the government, it has been multiplying missions abroad. An unfamiliar event, president Kabila ![]() made two trips, one to Egypt and the other to Gabon, where an Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) summit was held. The Foreign Affairs Minister Leonard She Okitundu travelled everywhere, to Egypt and Gabon, to Angola and South Africa (South African Development Community heavyweights), to neighbouring Burundi and Rwanda, to South Sudan, and the Central African Republic (CAR). The Congolese minister met the Chadian Idriss Deby, the Equatorial Guinean Teodoro Obiang Nguema, the Guinean Alpha Condé, the Congolese Denis Sassou Nguesso, the Algerian Smail Chergui, Peace and Security Commissioner of the African Union, and even the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Serguei Lavrov. This “active” diplomacy seems to have been productive. Thus, on 29 May 2017, when the European Union applied sanctions against nine prominent Congolese figures following the crackdown in Greater Kasai, 42 mass graves and videos of exactions, some African partners rebel, such as Angola.

made two trips, one to Egypt and the other to Gabon, where an Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) summit was held. The Foreign Affairs Minister Leonard She Okitundu travelled everywhere, to Egypt and Gabon, to Angola and South Africa (South African Development Community heavyweights), to neighbouring Burundi and Rwanda, to South Sudan, and the Central African Republic (CAR). The Congolese minister met the Chadian Idriss Deby, the Equatorial Guinean Teodoro Obiang Nguema, the Guinean Alpha Condé, the Congolese Denis Sassou Nguesso, the Algerian Smail Chergui, Peace and Security Commissioner of the African Union, and even the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Serguei Lavrov. This “active” diplomacy seems to have been productive. Thus, on 29 May 2017, when the European Union applied sanctions against nine prominent Congolese figures following the crackdown in Greater Kasai, 42 mass graves and videos of exactions, some African partners rebel, such as Angola.

According to Western diplomats, Russia and China will block any international investigation into the massacres. As for the Congolese government, it is willing to accept a joint investigation as it has already done for other cases. Kinshasa will maintain control of the process and the UN will be allowed to provide support as they have already done in the past, notably in 2013 for the massacre of Kitchanga ![]() .

.

Then there’s the UN Human Rights Council. Its High Commission hopes to obtain a an international court of enquiry during June 2017 session. At the previous session in March, African countries, including South Africa, blocked this initiative. Whatever the decision, in the name of sovereignty, it is out of the question for the Congolese government to accept an international enquiry, either into the massacres in Greater Kasai or the execution of the two UN experts, the American Michael J Sharp and the Swedish Zaida Catalan.

haut de page